“It is that you know that you are not supposed to be alive … The unnatural fact of living is something you must eventually fix.” She sees doctor after doctor, accumulating diagnoses and pills, but none of it makes any difference. During these episodes, it is not, she says, that she wants to die. They understand she is not well, that ever since “a little bomb went off in my brain” at the age of 17, she has been crushed by a recurring depression that leaves her, for days, weeks or months at a time, exhausted, terrified and unable to function. Her family sticks by her, Ingrid most of all. It is also something she cannot seem to stop.ĭespite all this, people forgive Martha – until, like Patrick, they can’t do it any more.

That she hurts the people who love her best is something that causes her great anguish.

She is also sharp-tongued, cruel, careless and prone to bursts of white-hot rage that range over the people closest to her like searchlights, mercilessly picking out their failings. Martha is clever, compassionate, hilarious, fierce and devastatingly sharp-eyed.

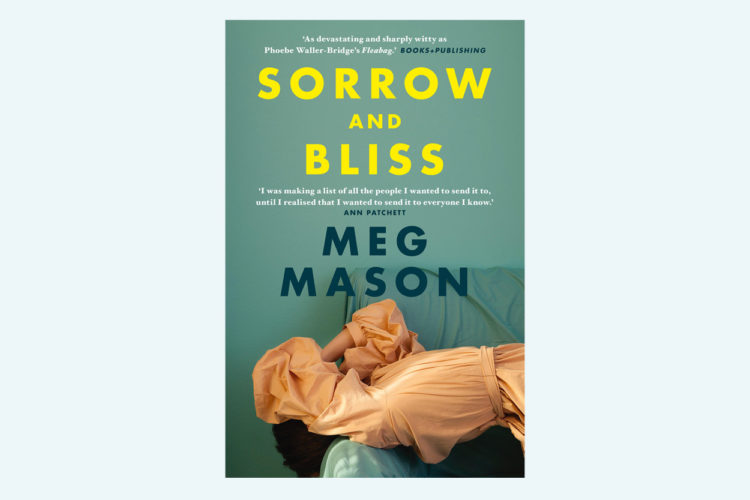

Eight years and several pages later, he leaves her. Patrick has loved Martha most of his life. Like so much in this gloriously tender and absorbing novel, Patrick’s remark manages to be both technically true and hopelessly wide of the mark. Recalling a party not long after their wedding, she remembers Patrick suggesting that, instead of staring at a woman standing by herself and feeling sad on her behalf, she should go over and compliment her on her hat. It is clear from the start, though, that Martha does not make things easy. She has few friends, but is intensely close to her sister Ingrid. Martha Friel is 40, the writer of a “funny food column” that, once her editor has cut out all the jokes, is – as she sardonically acknowledges – just a food column. In Sorrow and Bliss, New Zealander Meg Mason’s first novel to be published in the UK, it falls to the dancer to tell her story as she sees it, even as she dances closer and closer towards the abyss. In fiction it is usually the watching sister who takes on the role of the storyteller. It is a pattern familiar from life and from literature. I n her poem “Tango”, 2020’s Nobel laureate Louise Glück concludes that “Of two sisters, one is always the watcher, one the dancer”.

0 kommentar(er)

0 kommentar(er)